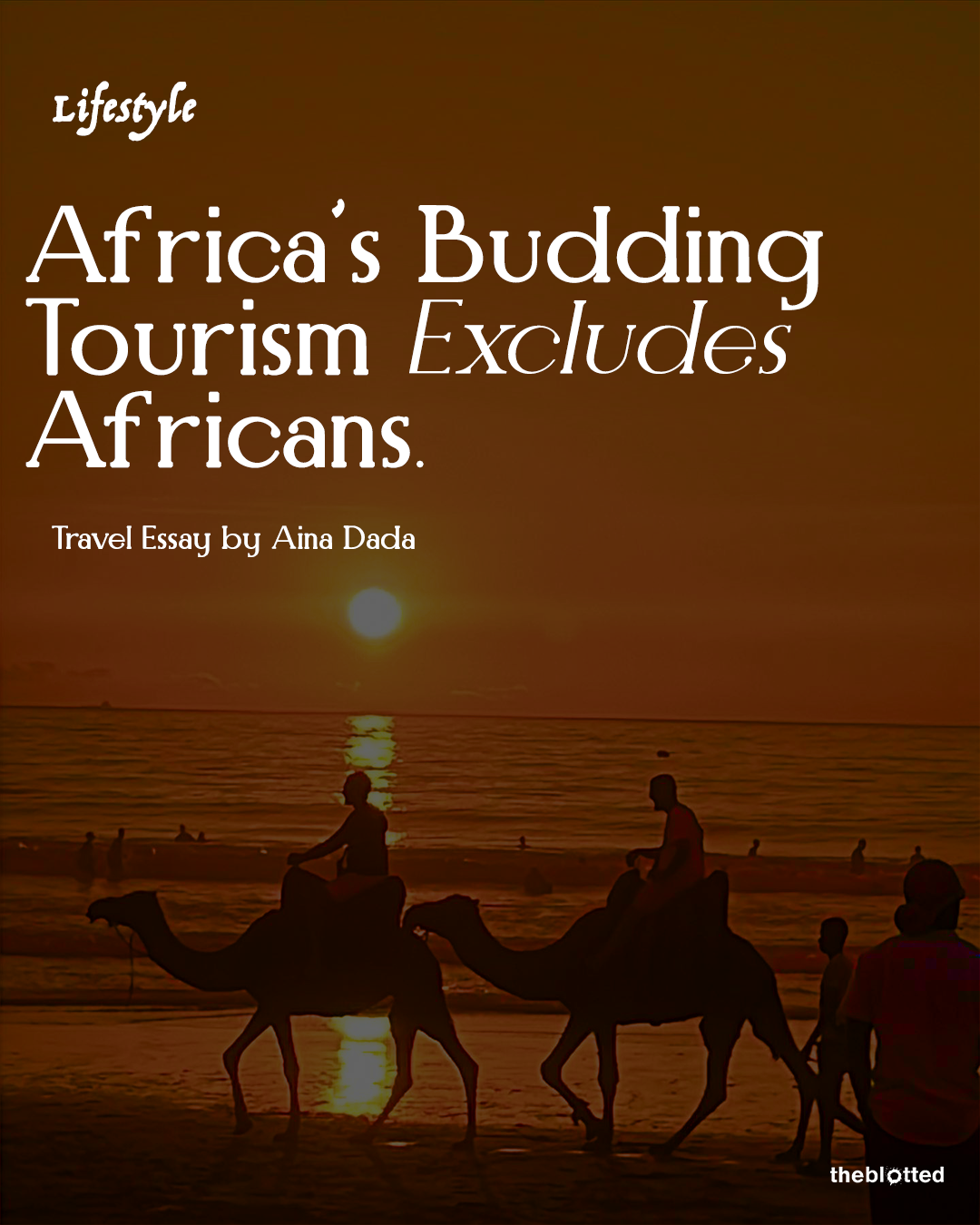

My last trip to Kenya was my first time solo-hosting a group. As a travel guide, I was all too familiar with the ‘process’, and decided to avoid ‘trouble’ by boxing up my usual oldest shirt and sweatpants which I find awfully comfortable. I wore a jumpsuit and an expensive Mark and Spencer sweater on top. A decision that nearly bumped me from economy to business class. Two days later my first two clients would arrive from Lagos and experience a less smooth entry. At Mombasa airport, they were singled out from the queues and searched. Bribes were exchanged and they almost missed their onward flight to Nairobi. In stark contrast, our last travel partner would arrive from America and as you can expect, his entry was a breeze.

While most African nations gained their independence from the mid to late 20th century, tourism to the continent has remained a Western– and more recently Chinese-oriented industry. It’s only now that covid has brought the lucrative international tourism trade to its knees that African travelers are stopping to reconsider their domestic markets. But there are huge logistical and financial hurdles to African domestic and internal travel, many of which are so far removed from mainstream tourism that they’re usually taken for granted by our international visitors.

For starters, there’s the question of visas. Even when traveling within the continent, African passports don’t command as much respect (if any), as Western ones. The 2019 Visa Openness Report, compiled and published by the African Development Bank, revealed that Africans need visas to travel to 49% of other African countries, and require e-visas on arrival for a further 26%. The African Union has advocated for the Africa Passport to make intra-Africa travel much easier, but feet are being dragged, as with anything that requires bureaucracy. The sheer cost of visas, priced in dollars for the international market ranges from $50 to $200. For those countries that don’t issue e-visas, a visit to an Embassy or High Commission is required, increasing costs further.

In a journey marked by numerous firsts, even for a seasoned traveler like myself who has wandered Kenya’s expenses before, the captivating essence of Africa’s diversity remains unmatched. Within the Faraway, a travel community I co-established, our compass unfailingly points toward fostering human connections. As a result, our initial preferences are Airbnb havens and intimate boutique hotels. Places that seamlessly blend elements of communal privacy and personal sanctuaries.

I thought the locals would have special knowledge of the land and the best places to stay, and they did. But I was surprised to find out that these places were actually owned by Asians, Arabs, Europeans or Americans, who own the most beautiful and exclusive spots. Looking deeper, I discovered something puzzling about Kenya – places meant for animals’ protection and even islands were owned by outsiders. So, Kenya’s story, a microcosm of Africa’s, is intricate, with each layer showing a new aspect when you look closely.

This naturally raises a significant conversation about controlled access to certain experiences. During our journey, we attempted to reserve an Airbnb in Naivasha. We inquired about the quality of the wifi signal and whether additional internet might be necessary. Surprisingly, the host, a white woman, promptly turned down our request, stating that the property wasn’t suitable for us and our friends. Yet, when we made the request again, this time using a female account, she accepted. Quite perplexing that even on Airbnb, as a young man, especially a Nigerian, you encounter a certain level of scrutiny and suspicion.

There are several of these properties in Kenya’s most sought-after precincts, which means if my host doesn’t think for any reason I deserve access to an experience or a slice of a continent, mine–I will never be able to reach it. This experience also led me to discover Kericho gold, the famous tea company, and its interesting story. Kericho Gold, like many British tea companies now operating out of Kenya got those lands by violently displacing the locals who own the land, and they took it a step further by bringing them back to now work on those lands for a little wage while exploiting the women for sex.

In several essays, these stories are told, with some of them happening as recently as 1970, which means the people who endured this torture and had their lands grabbed are alive, and have become slaves in their own homes. It’s 2024, and the suffering still continues with talks of reparations that have no end. It is highly unlikely that these lands will ever be returned to the original owners with many of these lands being further claimed by first and second generation settlers insisting it is their family heritage and guarding it as such.

Unfortunately, the discrimination doesn’t end with difficulty booking accommodation on Airbnb, Africans are priced out of their own tourism industry in all sorts of other ways too. Air travel is more expensive with fewer discounted flights and connections than, say, intra-European travelers are used to. Moreover, the very essence of the tourism industry has been tailored across the continent as a luxurious, high-stakes escapade catering primarily to affluent foreign clientele. Safaris, an embodiment of this exclusivity, carry a price tag reaching into the hundreds of dollars per night, a steep expense that even Westerners find daunting, let alone the majority of Africans, who are left with these grand adventures beyond their fiscal grasp.

The problem doesn’t end at tourism as more and more these issues are beginning to eat deep into the everyday lives of the locals. There are several types of NGOs springing up daily with expats serving as the majority of their staff. Go to Senegal, Kenya, Tanzania and take a stroll through the choicest areas and you’ll find those areas dominated by foreigners with little to no locals. Due to their earning power, they’re driving up the cost of living and accommodations in these areas, eventually creating some form of segregation and phasing locals out of certain regions because they simply can’t afford it.

Taking it a step further, these expatriates delve into ventures within less regulated sectors. In an ironic twist, the businesses they launch often fail to align with the needs and preferences of the African market they ostensibly serve. I remember my first trip to Lamu in Senegal. It stood out to me that it felt like the white man’s land. This impression was so pronounced that during a dinner outing, my companions and I found ourselves the sole black patrons in a bustling restaurant. and everyone kept staring at us as though they were wondering if we couldn’t read the room, and perhaps find a blacker spot to eat.

Aside from cost and logistics, there’s an intangible but enduring side to African tourism and travel writing that maintains an ominous sense of segregation. Guidebooks and travel writing typically focus on Africa’s natural heritage at the expense of its cities and contemporary urban culture while the imagery and language of tourism marketing, especially safari, remain overwhelmingly oriented to wealthy foreign travelers. As Ayomide Aborowa, founder of Lagos-based Irin Journal, puts it: “We are not the target market. I don’t feel welcome or invited.”

The Writer: Aina Dada is a guide, digital nomad with over seven years of travel experience across West, East and North Africa. She currently runs The Faraway, a Lagos, Kenyan based travel agency.

NO COMMENTS