Pencil to Pixel: Kayode Onimole & The Nigerian Visual Comics

Kayode Onimole’s trajectory as an artist scrambling against odds is a quintessential story for practitioners in the field. The average Nigerian illustrator is underpriced and undervalued: to be successful in this profession, one must be multifaceted; you must draw comics, create storyboards, design logos, and create corporate designs. And even after all is done, success is greatly hinged on an ‘if’ factor.

Kayode, was born into a family of four, with mainly his mother and youngest sister channeling their artistic sides through the the culinary arts and baking. He grew up influenced by legacy Nigerian cartoonists. Oguntade Morak’s ‘Omo Elewu’, who used daily comic strips as knife to slice political tension, while Moses Ebong from the Punch wielded pencil as weapon for satire, poking holes in the fabric of societal constructs that we have grown to ignore.

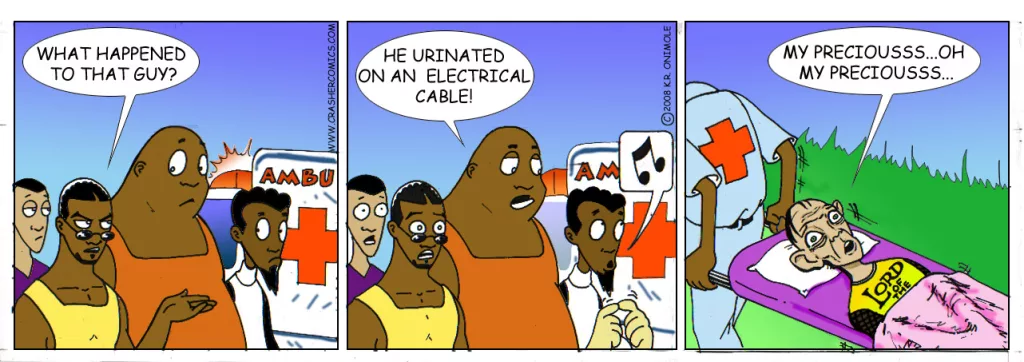

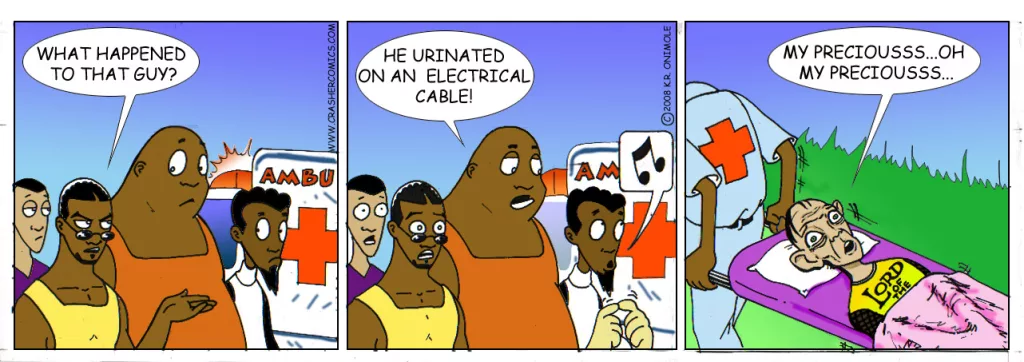

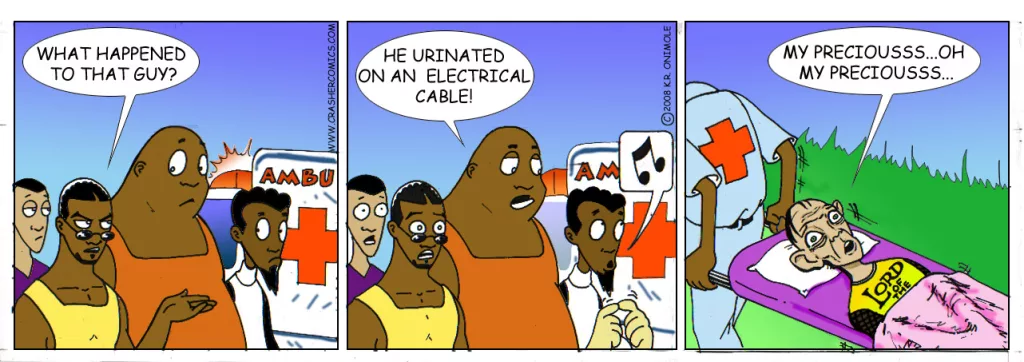

He got a significant break into creating comics while he was in charge of the Student Architecture Department notice board at the Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife Osun state. Here, he conceived ‘Crasher’: a weekly strip series based around a slacker architecture student. It proved so popular within campus that Kayode decided to expand it. He tried various newspapers to no avail and finally decided to make it a webcomic , Crashercomics.com.

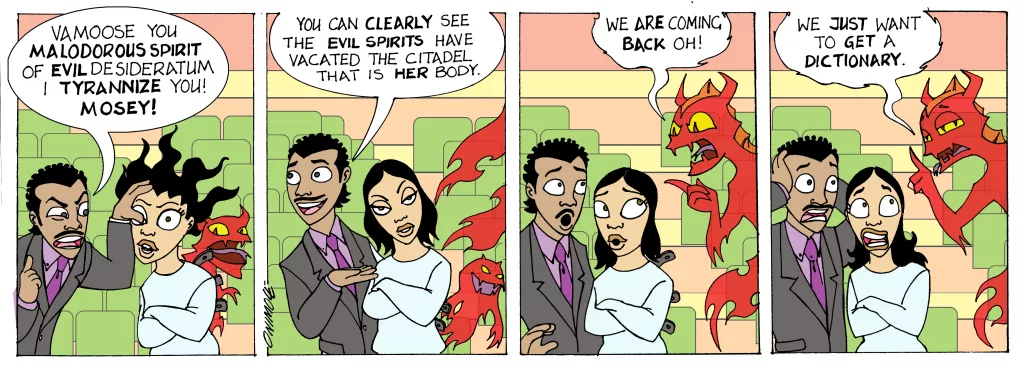

Crashercomics, Kayode Onimole

Crashercomics, based in Obawon University, is described by the site admin as ‘A love story at its core,’ and it was a groundbreaking sensation at the time. Being ingrained as a part of Nigerian youth culture when it was released in the late 2000s. A new issue would drop every Wednesday for over ten years. It was awarded The Comics Choice and Critics Awards fan choice at Comic Con in 2016. Crasher comics even got a paperback release in 2014; and also partnered with Etisalat to deliver strips to mobile users who would care to subscribe through text message.

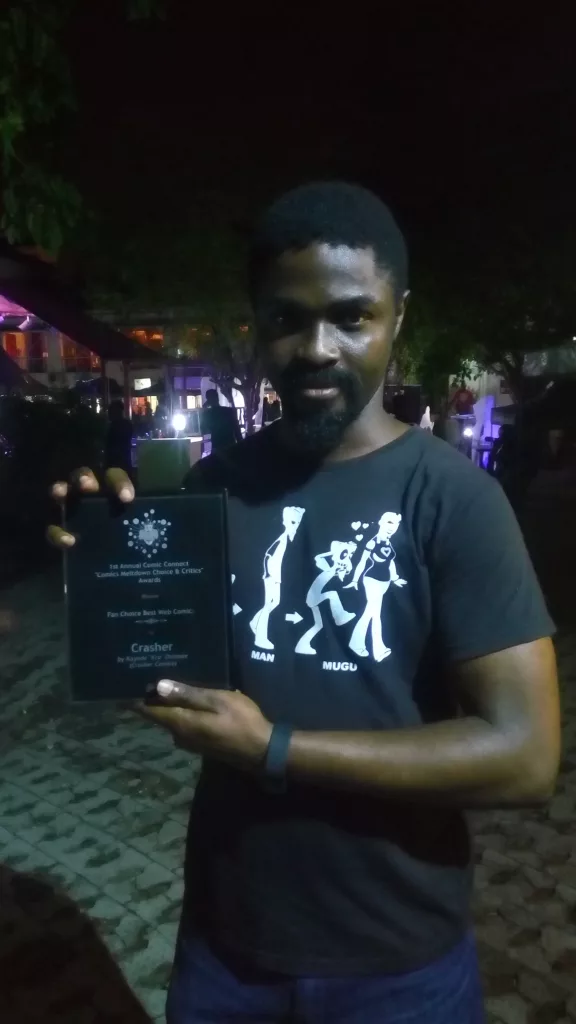

Kayode Onimole holding his award, 2016

Crashercomics is satirical and observational in its delivery. What you would consider as a love child of early 2000s Nigerian newspapers, and spiritual ancestors to newer bitesized webcomics like Justin Irabor’s Obaranda. The strips are colorful—character lines are thick with little in the way of shading to create depth. The topics are imaginative, sometimes pop culture-oriented, sometimes urgent—depending on what happened recently or what Kayode finds funny. These strips and style were even featured as part of The Guardian Life Nigeria for weekly publication for a period. There, Crashercomics received its widest viewership yet and a lot of censorship as well. “I made fun of some of their advertisers and I don’t think they liked that” Kayode said “But you live and you learn.”

Cartoons haven’t exactly been held in prestigious regard throughout Nigerian publication history. Apart from the provocative and risque Ikebe Super series, which was consumed heavily in the 90s, comics have been relegated to cameo appearances within newspapers. And even these papers do not see it fitting to bring along the cartoons as they cross over to a digital ecosystem. Most of these strips are lost in paper print, and a lot of the talents have served their contracts and moved on to other areas of expertise or greener pastures. In fact, the Crashercomics website is currently inactive, but Kayode declares he will once again return to this initiative sometime in the future.

The past, present, and future might seem bleak for comic commercialization in Nigeria; yet, it is interesting to note that Supa Strikas, a football-based series, lays a strong claim as the highest-selling physical media in Africa—printing over 1.7 million copies every month. Its longevity and reach can, however, be credited to numerous sponsorships and a subsidized price tag only a million assured sales can promise.

There are concerted efforts to celebrate and platform artists creating comics in the country, for example, Ayodele Elegba’s “Lagos Comic Con” (Not to be confused with Comic Con that awarded Kayode in 2016), which has grown into a niche cultural event. However, the economics haven’t worked out yet, and most illustrators have not found it lucrative enough to sustain themselves. One can’t even point to a single Nigerian comic that has garnered a cultural following that can rival Ikebe Super, Crashercomics– much less Super Strikas.

In conversations with The Blotted on how the Nigerian space can capitalize on its love for visual stories, as the Japanese have done with Manga and anime, Kayode Onimole expresses that it is a matter of knowing one’s audience and providing relatable stories. Sponsorships and creating an enabling environment for people to succeed, and most importantly, fail, will also play a role in this.

While Kayode intends to continue Crashercomics sometime in the future, he continues on the path of telling stories vital to the human experience. In 2018, he illustrated ‘The Greatest Animal in the Jungle,’ written by Sope Martins, and ‘There is an Elephant in my Wardrobe,’ by Yejide Kilanko– both published by Kachifo. He has gone on to collaborate with playwright, novelist, poet, and Ake Fest Convener: Lola Shoneyin on their Northern lights series of books that aim to encourage reading in the Northern part of Nigeria. It includes such titles like ‘Do as you are told Baji!’ and ‘Anyibou and the Mother Hen.’

Crashercomics, Kayode Onimole

The roles illustrators have historically played have always been communicative. The earliest forms of communication in the Egyptian Hieroglyphs have glossaries where the words bear similarities with the objects being labeled. Even the earliest forms of expression, found in the Lascaux caves, were illustrated works of art—from 17,000 years ago. They are used to tell stories, to educate, to stamp a mark of presence. Illustration’s role as a human necessity yet endures and spread across ages, demographics, and language barriers; it will never run out of style.

Kayode has worked on numerous projects, using his art as a means to communicate reductively—skills that require lots of jargon. He was commissioned by the Nigerian Stock Exchange to work on Stock Town, a series of comic books that aim to teach young people how the market works. And also, Lola Shoneyin’s ‘Me and my Money: Financial Literacy for Kids,’ a guide to managing money sponsored by Sterling Bank. Both books are still being given out for free.

His work process varies from client to client; sometimes he gets a synopsis from the client on what is needed, and then he develops characters to build stories around them. However, recently, Kayode has found it more effective to work directly with writers to get a better sense of their vision and researchers so that he’d be able to add a level of depth to his works.

Crashercomics, Kayode Onimole

Kayode Onimole’s career has evolved with the times and terrain. His specialty and passions follow suit as well— from one pet project becoming a Nigerian darling to opening numerous doors of opportunities. Kayode’s story shows that illustrators yet remain an important part of our creative and public relations workforce. They may not yet witness the radical cultural shift their ideas deserve, but it is possible to be empowered enough to live off this profession and create a proper structure for coming generations. One probably will just have to prove themselves first.

Read more reviews and pieces about culture and art on The Blotted. Follow us on Twitter and Instagram @onetinyblot

Onimole Fuad Adewale August 13, 2024

I’m interested in this