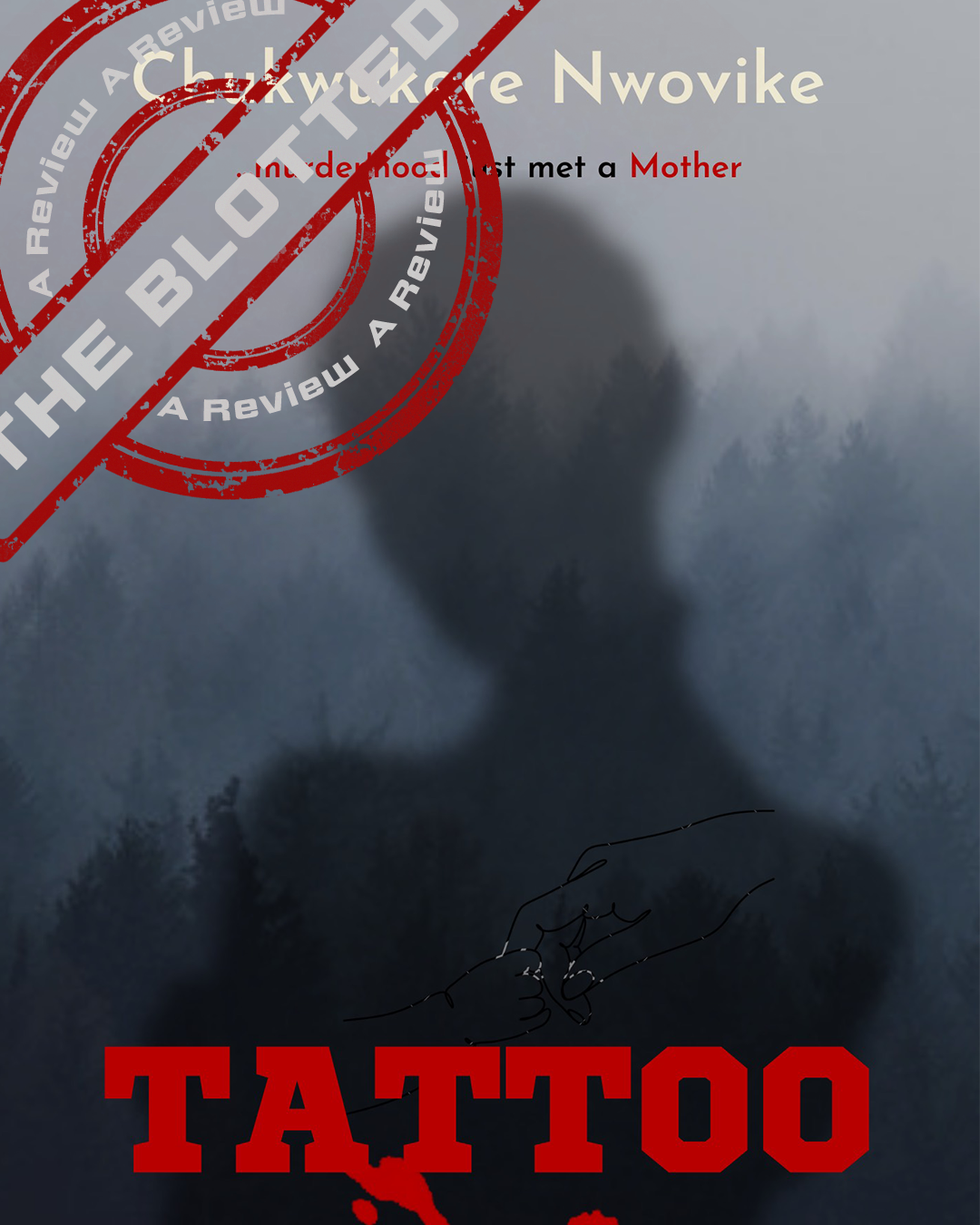

Tattoos Are Memories in Ink: A Review Of Chukwukere Nwovike’s Tattoo

They say the simplest things are sometimes too tedious to understand. There is the fact that all living things must die, and the saying that birds have wings for flight, and all birds have wings, but not all fly. I find the person of Chukwukere Nwovike even before publishing Tattoo to be similar to this analogy of simple complexity. He is taciturn but accommodating, a loner with a relatively outdoorsy Instagram page. And this shows in the way he writes about simple, relatable themes of life with twists that can keep a story running on line unending.

In Tattoo, a woman is stripped of her last treasure. The single thing that could possibly give her life meaning is snatched right from under her nose. As is the nature of grief, she feels her world become undone. She neither wants to let go, nor know how to stay still. There is a certain motion about her with the world returning to normalcy, and her ability to feel things other than grief, such as anger and sexual desire. Yet, nothing is the same. The world— at least hers— moves with the stillness of midnight; you hear the clock tick, but the night remains static, encompassing silence and engulfing blackness.

There is a certain craze peculiar to grief. It is that state of being where one seeks closure, yet trembles at the thought of what comes after. In her bid to find answers, no matter how unpleasant they may be, Ada adorns courage on her creased forehead, while wearing her fragile heart on her sleeves.

The story compels one to look inward as they journey with the characters. There is something almost philosophical about the narrator’s search and findings. Throughout the events that unfurls, there is an emotional taunting (either deliberate or not) that stands out as brilliant. One minute you forget that this is about a grieving woman unable to count her losses, the very next you find your lungs clap short as you are reminded of the magnitude of her suffering.

It is such a rude awakening, a constant resurfacing of sorrows that we are quick to forget when they are not of direct consequence to us; in the story we find everyone sympathizing with her even though they are incapable of comprehending the state of her mind: you find another mother aggressively dismiss her son, a neighbour, grabbing the body of another man’s wife, an angry co-tenant raining curses and barking threats; all of these occur in a compound where the worst has happened and one of their own still mourns.

Similarly, there is something interesting about Chukwukere Nwovike’s writing technique. Such as his sublime reliance on simile, and his off-handedness. How seamlessly bare he allows emotions run between his characters. The conversation between the protagonist, Ada, in Tattoo and every other character (both round and flat) rides on the naked expression of her heavy heart. You peel through the pages of this story painfully, as the dialogue progresses the weight of sadness on Nwovike’s main character. The heaviness transcends the pages to wrap a cold deathly grip around the readers’ heart.

Though the narrator tells a compelling tale, I find the use of the word as, a little excessive, which at intervals might disconnect the reader from the story itself. But considering that it is a first man narrative technique, you likely would think the narrator speaks of the events in the way an average Nigerian citizen would. Personally, I do not think that’s what the author was trying to do because an average Nigerian would rely, more or less, on local dialects like pidgin English or her mother’s tongue.

However, in Tattoo the use of dialect is almost non-existent. This may not get in the way of some readers, but for me a significant amount of native language must be present in African literature (given the setting— such as if it’s a village or a rural area or a bus park) for me to fully immerse myself in the present location and lives of the characters on my journey with them on the pages they are imprinted on. For example, I think a sprinkle of Yoruba and not just broken English at the Butcher’s shop would have painted a more vivid picture or the employment of slangs later in the story at the point the area boys wined at a local bar where the albino beckoned to her would have been a solid delivery. Even though this are my personal reservations, it does not take away from the unputdownable effect Tattoo is likely to have on readers.

Chukwukere Nwovike in this work of art maximizes the advantage of suspense with the way he masterfully casts shadows on the credibility of each character, not sparing even a twelve year old boy from being a suspect. This is perhaps the best thrill I got from the story. The inability to decipher which of the characters was likely to do something so abominable and why. One of the elements of a good story is character flaw. Nwovike recklessly exposes his characters imperfections. He is an author who understands the difference between angels and humans, and we see this through his bold display of people with stunted personalities.

There are a series of themes meticulously explored in this work, ranging from grief, to parenthood, murder, cheating, and a number of other tangible issues. Ultimately, Tattoo talks about grief, loss, memories, and times when you think the world can possibly take nothing else from you, you realize there is yet so much to lose. What happens when your already shaky world upturns? What is the cost of knowledge that only breaks you further? If to grieve is to suffer, what becomes of closure that opens new wounds and puzzles? Chukwukere Nwovike prompts these questions in the mind of his readers, leaving them to fend for the answers in his harrowing, sorrowful tale. Here is a page turner, another story the world deserves to read.

Tattoo is available on Amazon and will be on Okada Books from the 13th of June, 2023

About the writer: Oluwatoba James Abu likes to think of himself firstly as a writer. Above all else, he believes in gender equality, advocating about climate change and in the existence of a saner world— where words like phobia and marginalized are redundant because there would be no need for them. His first publication is Fire Is For Silence, published by Afritondo Media and Publishing.

NO COMMENTS