Jester to Comic: A Billion Laughs’s Balancing Act in Nigerian Stand-up Comedy

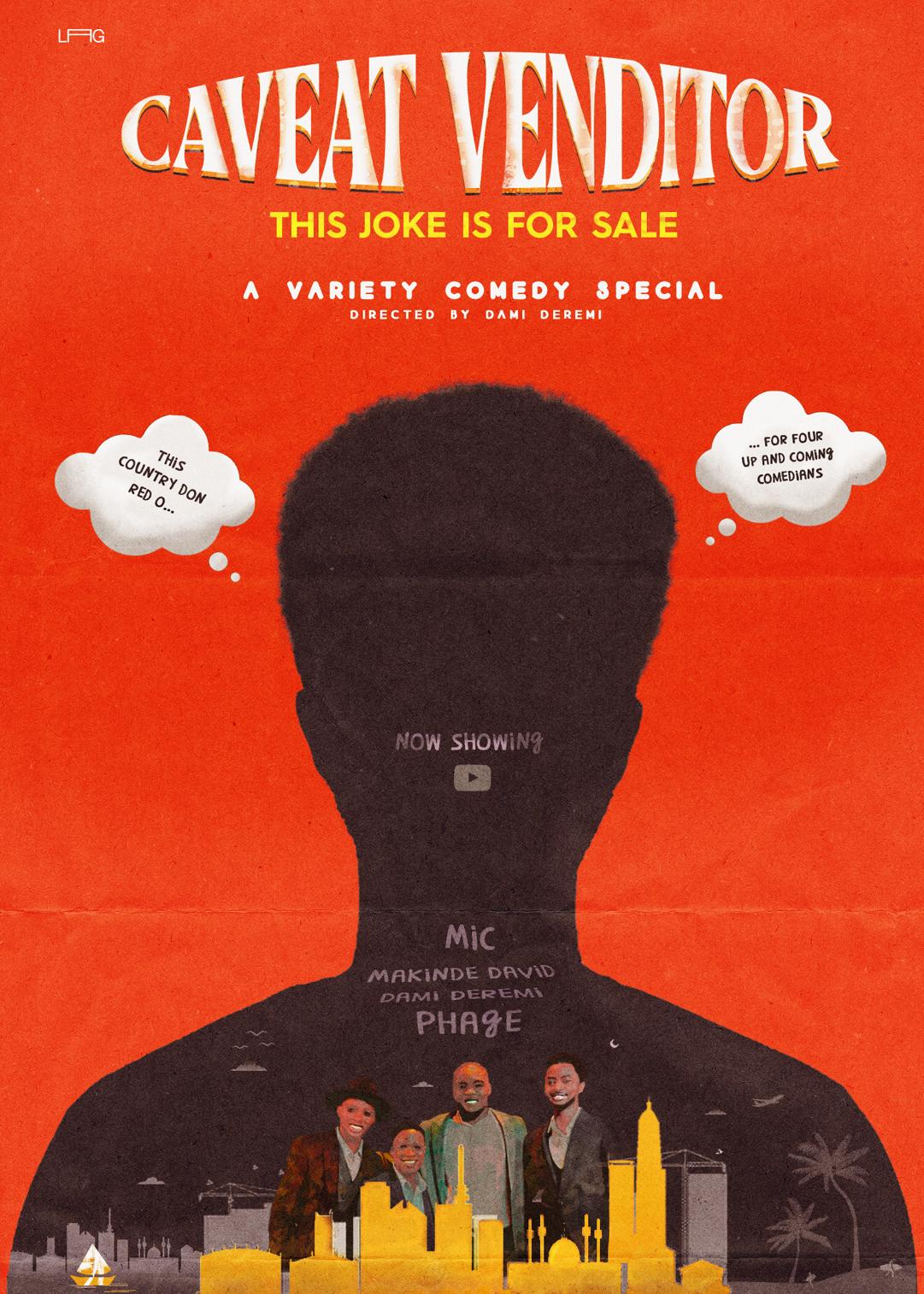

Caveat Venditor by A Billion Laughs is commentary on the comedy industry by practitioners who seem to exist on the outskirt of its mainstream. Their manifesto, which is the first piece of information that introduces the show goes “A documentary-ish variety special by four comedians you’ll probably never hear of”. The ‘Caveat quartet’, all-male, oscillating mid-twenties to thirties take turns to show a sold-out crowd in Lagos Fringe– and the ones peering through screens—a balancing act. On one hand, punching the art to a pulp in satire and the other, celebrating it as lovers of the craft.

It is a two-day variety show that attempts to demonstrate what Nigerian Stand-Up Comedy could be, if given enough leeway to evolve. Their sketches create caricatures of certain personality types in the industry. Singular Baba, in the person of Micheal Mic’ Akinsanya only has one joke in his repertoire, and he tells it at every opportunity he gets. He exhausts this ridiculous concept by inviting the audience to his personal show, where he would tell the same joke with different microphones.

Fejiro ‘Phage’ Omu plays Mr. Exposure, who satirizes the conventional show promoter behaviour that aims to fleece aspiring acts of their labour. Makinde David collects the Joke stealer award of the day. He is announced onstage by the anchor, Dami Deremi who says Unintellectual Property with so much disdain, that it teases personality. Makinde’s height is heavily contrasted with Dami’s and might come across as a punchline to a separate joke onscreen. Their delivery is heavy on irony and at every opportunity, tries to hold up a mirror to society itself. Crafting wit from the mundanities that Nigerians survive each day by exploring unspoken parts of our culture.

Stand-Up comedy is heavily ingrained into the Nigerian society. Masters of Ceremonies, anchors, and moderators tell slight variations of the same jokes to douse tension, and properly aid transition between program events. The funnier an MC seems to be, the more sought after they are. Even Iya Alagas moderating Yoruba engagement parties lean into humour to appreciate traditional marriage customs. For a population that ‘shies’ away from public discourse of certain topics. Jokes serve as the perfect vehicle to broach the necessary lewd, without seeming obnoxious.

All images designed Rebizm for A Billion Laughs

Even as it seems that the role of the stand-up comedian is being played by nearly anyone that grabs the microphone, a lot is left to be desired in how we have evolved the craft. From jesters to comics, Nigeria’s version of the ‘funny business’ bursted around the 1950s—where personalities like Samanja, Papa Lolo, a stingy and crooked Baba Sala and the Alawada crew amused audiences with drama sketches in-between what can be considered ‘more serious stage plays.’ Comedians at the time were actors, because that was the only platform available for them to shine.

Some of the Caveat sketches evoke strong call backs to the days when comics tried to show versatility on stage. To see a comedian go beyond telling jokes, and fill the shoes of a character is a style strongly amiss in mainstream comedy today. The last time an attempt at this became popular was A.Y’s long-drawn 2015 election night drama. Where he brought different practitioners to play Politicians. Although it failed to ask critical questions of the situation, the effort was refreshing. Ali Baba’s Spontaneity Show also attempted to expand the facet of improv comedy in Nigeria—but this hasn’t gotten much attention nationwide.

The Quartet’s approach to their craft is one of awareness. They poke fun at the complexity within the show title itself. They mock a niggling industry trend that causes comedians to shout their jokes to be funnier. Makinde, during a personal set still delivered his jokes in this style, and it makes you wonder; with their level of clarity on the clichés that plagued the industry—how can they toe the line they just satirized?

Mic is introduced by Phage as the longest practicing comedian among the bunch. It shows in his composure as well; he delivers his jokes like gists— unlike the others that take a free-form approach to their bits where you can hardly separate the end from setups, Michael’s punchlines are well defined. The Lecturer joke packed a punch, He perpetually rests one hand on his hip. Unless of course, when he wants to point and gesticulate.

The visual style is a direct nod to old American Comedy circuits of the 1970s. Black spots splatter the screen at intervals. Visual editing includes a mixed media effort that distorts key elements in the frames. A style that is not explored nearly enough in our delivery of documentaries. The stage is drab and reminiscent of a time long gone– when comics carried a certain gentleman-club charm with their craft. When they wore oversized shirts and told jokes that were accented by the drummer’s cymbal. The Caveat Venditor quartet also followed suit; pun-intended, there doesn’t seem to be much variation between their costumes in both days. Monochrome, plaid, suit and waist coasts.

Appearance has always been an important part of the art, and in some part, dictated this outlook of disdain that has followed the profession. Most comics that have tried to reinvent the craft have only been so successful at rebranding. JC (John Chukwu) for example came to prominence in the 1950s. He practically pioneered the craft in Nigeria, and since he was privileged enough to own Class Night Club Ikeja—stand-up comedy had its own platform. Ikeja’s neon-streets swooned with people who had acquired the taste, and found a likening to JC’s style. His improv, quick thinking and unique perspective to society kept him relevant.

All images designed Rebizm for A Billion Laughs

An anonymous user on Nairaland submitted a surviving joke of his:

“Remember the last time I was broke, you helped me out and I said I will never forget you?

Yes

I am broke again”

JC dressed better than other comics, he was dapper, almost enviable—unlike the first-generation comedians that dressed to jest. Ali Baba also made similar strides in rebranding the craft. The Caveat four strike the same feeling as early-generation comedians did. But not because they didn’t put effort—but because they looked odd. You only see that many young men, formally dressed gathered at the waiting room of a hiring agency. This choice of style is especially effective when Phage jokes about being jobless despite graduating with a Human Resource Management Bachelors at Covenant University. Or Mic’s bit about the one time his father tried to intervene and suggest a better trade.

Waist-coat wearing, afro-toting Dami Deremi plays the host almost through the clip. In the Roast Session, he is introduced by Phage as the most popular comedian we do not know. He strikes one as a fascinating character and Phage’s bit on his Caucasian wife received one of the best howlers of the night. He starts out his set translating the show’s title to ground character and meaning. You kind of get the impression that he is one of the major brains behind putting the show, and documentary together—this is correct, he is the founder of A Billion Laughs. He even gets serious mid-joke to canvas awareness about the state of affairs at National Stadium in Surulere. Granted, he did that after a merciless 3-minute tirade of non-stop roast.

Makinde makes a habit of turning the joke on itself, during his personal bit about how jokes don’t exist anymore. He stares down the audience and asks them if they think his own performance was not stolen from another lad in the comedy circuit. That surreal, and meta moment perfectly idealises the Caveat Venditor ‘approach’. The wit is dry and self-aware. Phage’s delivery is almost dead-pan. He is self-deprecatory with his observations. The first time Phage is introduced onscreen, he calls himself overweight after refusing to jump off a trampoline when he had his fill with it. He is hesitant with his delivery, and this adds to the charm in his jokes. His style, which is reminiscent of American comic, Louis CK endears the audience to his person—and he shyly tangoes their affection with honest repartee.

Beyond hard realizations about the comedy industry, the Caveat Venditor sketches also offer biting commentary on the Nigerian political landscape. Comedy makes it easy to offer criticism without coming off trite. During the panel session—Makinde revealed his foray into comedy as an art, was borne from a desire to become a Nigerian politician. This remark is caustic and brutally honest.

Gone are the days, when comics could make keen observations about politics whilst retaining a sense of believability. Real life incidents, like the NDDC Managing Director ‘convulsing’ while being grilled on illegal spending and fund mismanagement. Or when Government officials claimed a snake swallowed a few million naira from state coffers have dulled expected potency comedy should possess.

All images designed Rebizm for A Billion Laughs

With the election of Donald Trump in 2016, even comics in the abroad found a hard time creating material that evoke strong emotional connection. Louis Dreyfus’ Oval Office satire, Veep, found its own exaggerated reality struggling to keep up with real life. Veep felt a lot safer, and saner—and inadvertently, more boring. But that’s not to say comedy has outlived its substance in our waking life.

Humour thrives the best in environments of political conflict and Nigeria is no stranger to these. In the 80s, during the height of the Soviet Union. Anti-government propaganda was likely punishable by death. Activism emerged in the few creating jokes that satirized the jackboots that stomped on the people’s necks. This culture of humour greatly salved the dwindling morale of the Soviets, who—otherwise would not be able to express their opinions. One of such jokes describes how a judge walked out of his chambers laughing. A colleague approached and asked why he was laughing. “I just heard the funniest joke in the world!” the Judge retorted. “Well, go ahead, tell me!” says the other judge. “I can’t – I just gave someone ten years for it!” Same can be said for Nigeria’s Police state, which is disguised as a democracy.

The demand for experiments to evolve the craft has never been more dire. But there persists a pressing issue on how lucrative passion projects will pay off, especially considering the time and resource it takes to document them like this. Nigerian comedy has been completely decentralised; with the internet snagging a substantial fragment of attention given to Stand-Up comedians. Instagram and TikTok comics show creativity, and proper blend in their approach. Personalities like @Maraji juxtapose adept video editing with social-observant sketches, @TherealFemi expands our humour palette with parody, witticism and news-style satire popularised by Jon Stewart and Late Night Show cohorts.

It is easy to assume that the industry is oversaturated. This sentiment might hold value, because even though the Nigerian comedy arm comes only after the film and music industry as regards revenue. It has nevertheless, witnessed drastic shrinkage over the past five years. In 2015, Osae-Brown reported a worth of N50 billion annually, and by 2020—Information Minister Lai Mohammed revealed it brought in N17 billion annually. It is almost certain, however, that the internet generation’s valuation has not been factored in.

Phage jokes about it during the panel session, calling parents that encourage their children to take up the craft irresponsible. Truth is, a lack of structure makes it impossible to earn a moderate living off stand-up comedy. One is either big enough to acquire stardom, or starving. And that is why Dami Deremi’s final question– which asked the remaining 3 ‘what they would do if offered 100 million naira to leave comedy’– closes off this charade of irony on a high. I leave the answer to your imagination.

Watch Caveat Venditor Here

All images designed Rebizm for A Billion Laughs

Read more reviews and pieces about culture and art on The Blotted. Follow us on Twitter and Instagram @onetinyblot

Olamide November 20, 2020

Now I want to see the show. A beautiful piece.